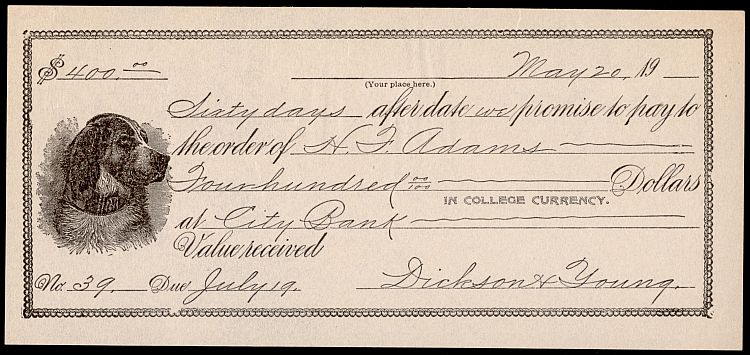

by Bob Hohertz

Our family is fond of dogs. When I mentioned to my oldest daughter that I didn’t have a lead article for this issue, her suggestion, at least partly in jest, was to write about dogs on checks. Since I’ve never tried to form a topical collection, the idea didn’t set too well at first. However, as time passed and no articles of sufficient length to serve as the lead were submitted, I began to think seriously about the project. How would I go about collecting dogs on checks if I were going to do it?

Looking over my own collection, largely consisting of revenue stamped paper, several uses of dogs became apparent. First, there are checks where there is a major emphasis on the dog as part of the design. On others, the dog is only one element of a vignette. The dog, guarding a safe and key, as a symbol of security and fidelity is reasonably common, and the almost incidental use of a dog’s head is probably meant to suggest these ideas. Finally, checks from dog breeders and kennels would be included, if I had any to show, which I don’t. I may buy one if I ever see one.

I’ll illustrate each of the first three concepts in turn. While the function of the dog and safe vignette may be unique to this topic, the other usages ought to be general enough to suggest ways to set up a topical collection.

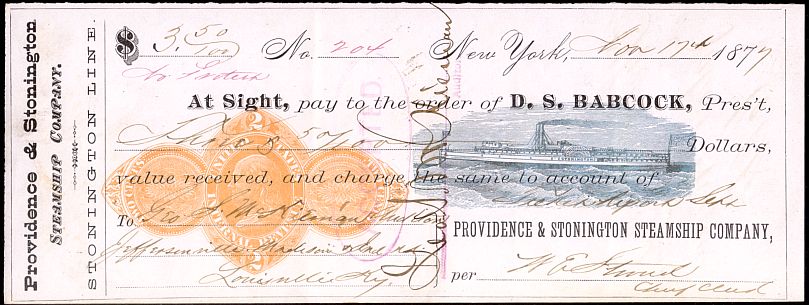

The Dog as Design

Figure 1. This rather brainless looking hunting dog with the snipe flying right over its head can’t possibly be meant as a symbol of safety. On the other hand, the unused check on the St. Louis Exchange Bank is a rather handsome one. It bears an RN Type C in orange with the extra wording, “Good only for bank check” in the design.

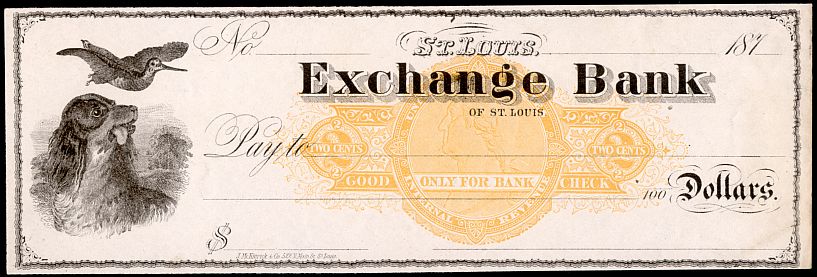

Figure 2. The dog on this check does not appear to be indictive of any symbolic meaning. (But see the 2007 Postscript.) The check bears an RN Type B in orange.

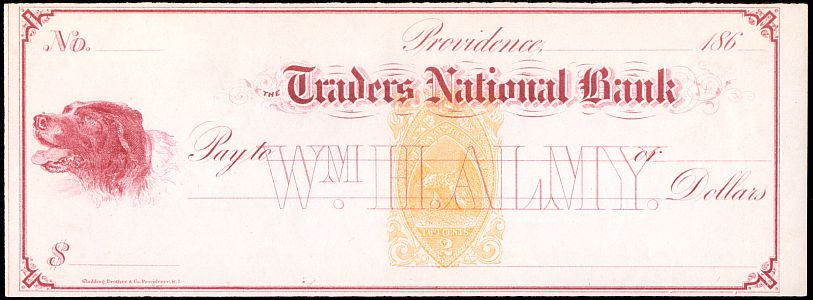

Figure 3. This item is a college exercise draft, payable “in college currency” sixty days after date. The dog is purely decorative.

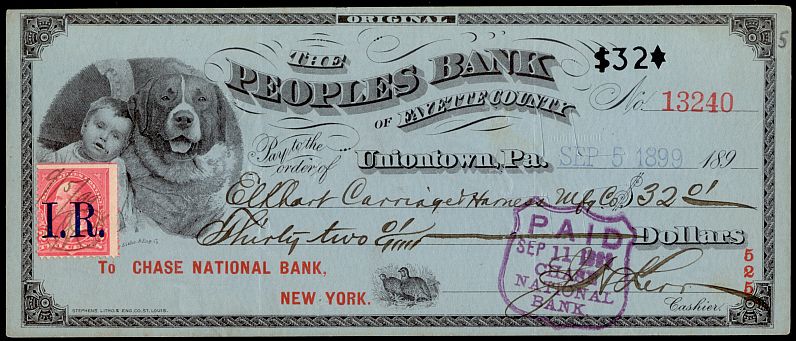

Figure 4. While the dog on this draft may be decorative, the presence of the young child also may imply a protective role. It was made out to the Elkhart Carriage Harness Mfg. Co. on September 5, 1899.

Figure 5. This check is one of a series that featured Norman Rockwell paintings of a boy and his dog. I used it in 1983 to pay for stamps purchased from the late Elizabeth Pope, a Past President of the American Stamp Dealers Association and a longtime philatelic mentor.

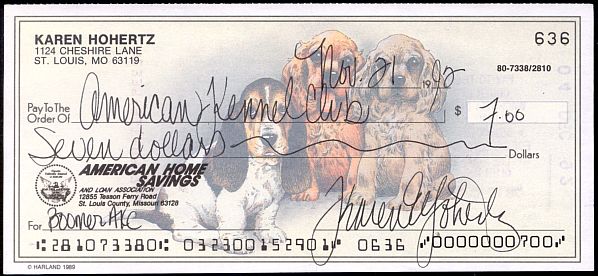

Figure 6. The puppies on this check are certainly meant for decoration only. My oldest daughter, Karen (an ASCC member), the one who suggested this article, used it in 1992 to pay for registering her purebred golden retriever.

The Dog as Incidental Design Element

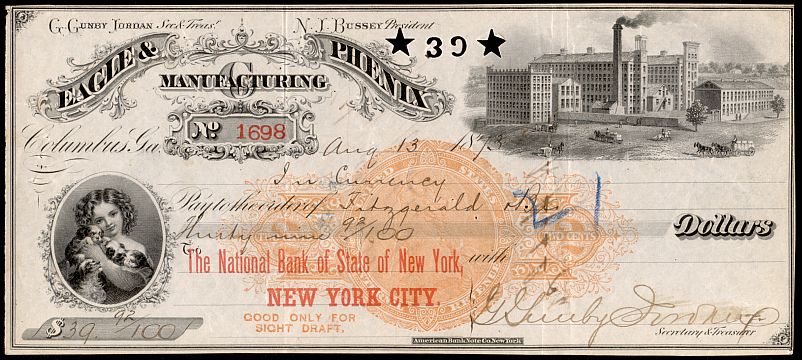

Figure 7. This beautiful American Bank Note Company item appears to be a check, despite the presence of an RN Type C with the extra wording “Good only for Sight Draft” at the lower left. It was used by the Eagle and Phenix Manufacturing Company of Columbus, Georgia, drawn on the National Bank of the State of New York. The vignette at the lower left hand shows a young girl holding several puppies. This vignette appears on at least one other engraved item in my collection.

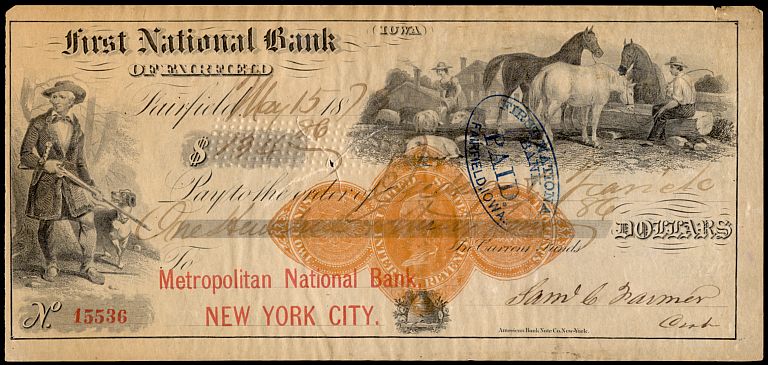

Figure 8. Another American Bank Note Company item, this one a draft originating on the First National Bank of Fairfield, Iowa. The hunter at the left is accompanied by his faithful dog. The imprinted revenue is Type D.

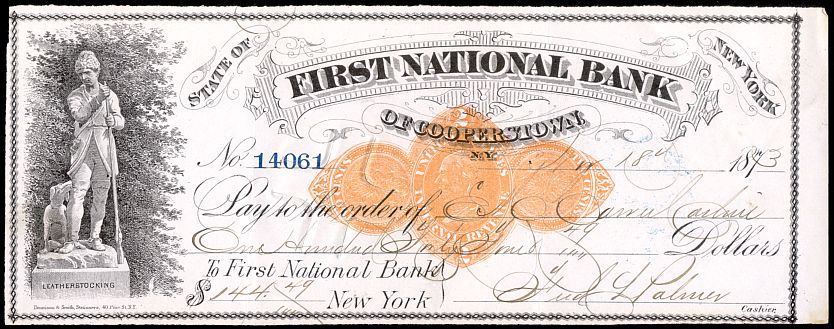

Figure 9. There are several versions of these drafts from the First National Bank of Cooperstown, New York, in different colored backgrounds and bearing different imprinted revenues. They are known with Spanish American War imprinted revenues as well. The design is the Leatherstocking statue, complete with dog.

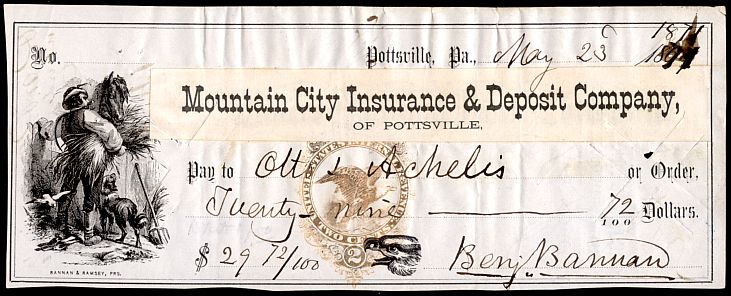

Figure 10. The dog on this check accompanies the man feeding a horse. The check bears a paste-over change to the Mountain City Insurance and Deposit Company of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, partially covering the Type H imprinted revenue.

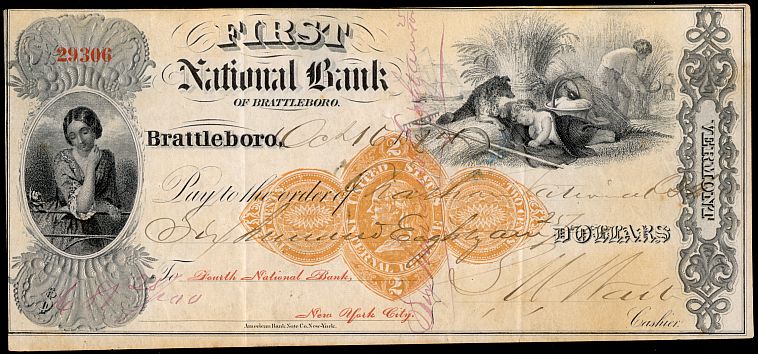

Figure 11. This handsome draft from the First National Bank of Brattleboro, Vermont bears a vignette that shows a dog relaxing with and protecting a sleeping child. Again, it was produced by the American Bank Note Company and contains a Type D imprint.

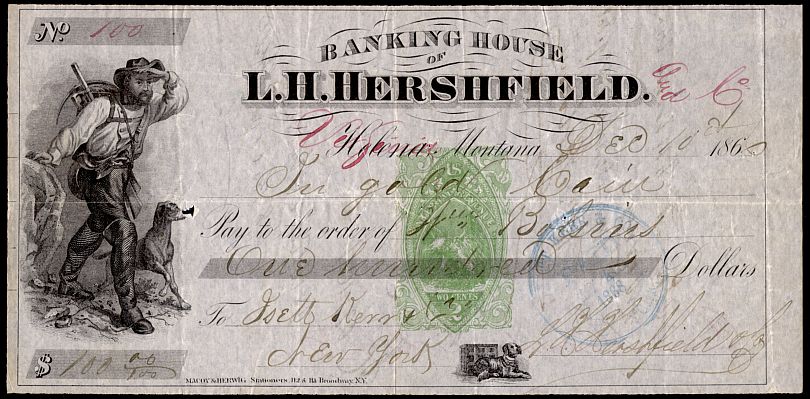

Figure 12. This draft on the Banking House of L.H. Hershfield was originally intended to be used in Helena, Montana, but was altered to read “Virginia” Montana. It is payable in New York “In gold coin.” The imprinted revenue is the green Type B.

This item belongs in the “Incidental Dog” category by virtue of the one accompanying the prospector. It also has a small “Dog and Safe” at the bottom, which brings us to our next topic.

The Dog, the Safe and the Key

In the last issue of The Check Collector (January – March 1977), Lee Poleske contributed an article called The Dog and the Safe, in which he discussed the Landseer portrait of a dog on a stone pier, the basis of the common vignette of the dog beside or on a safe. The classic design was used as early as 1877 and as late as the 1930’s.

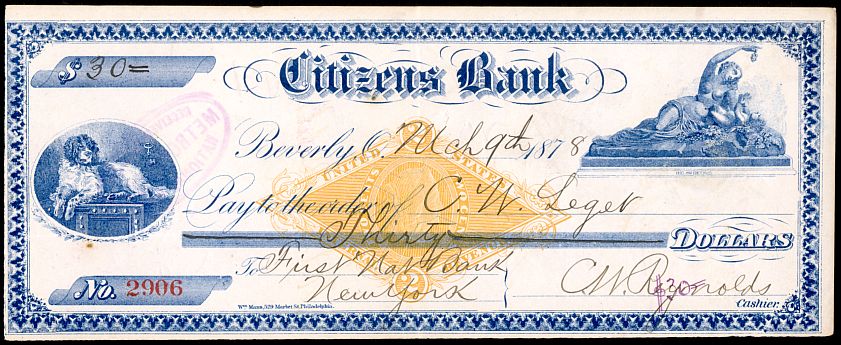

Figure 13. This Beverly, Ohio draft contains a particularly striking example of the “Landseer” vignette. It was printed by William Mann of Philadelphia.

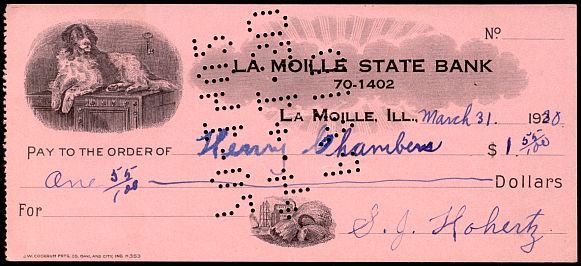

Figure 14. This check was used by my grandfather in 1930 to pay a bill of $1.55. The Landseer vignette is little changed from the 1870’s version. The check was printed by J.W. Cockrum and Company of Oakland City, Indiana.

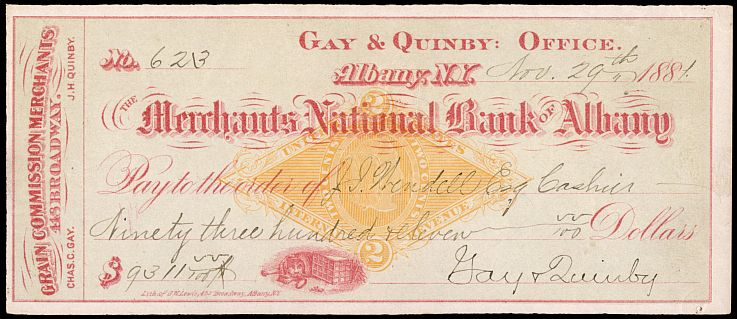

Figure 15 shows a different form of the basic dog, safe and key motif. This dog is lying partially behind the safe, with one paw on the key. The check was lithographed by G.W. Lewis of Albany for Gay and Quinby, Grain Commission Merchants. It was used in 1881 and bears a Type G imprinted revenue.

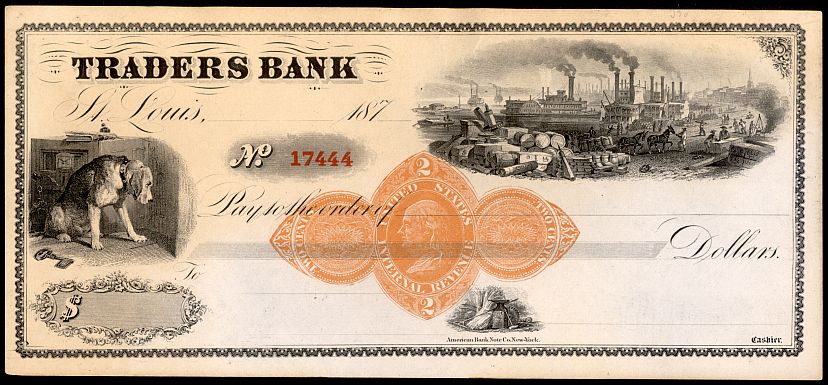

Figure 16 shows a clever variation on the theme. The dog is a major design element, but he’s something like a rawbone hound rather than a classic Landseer Newfoundland. He does guard (?) a safe, though, and the key is lying there being ignored. The American Bank Note company must have had fun designing this draft!

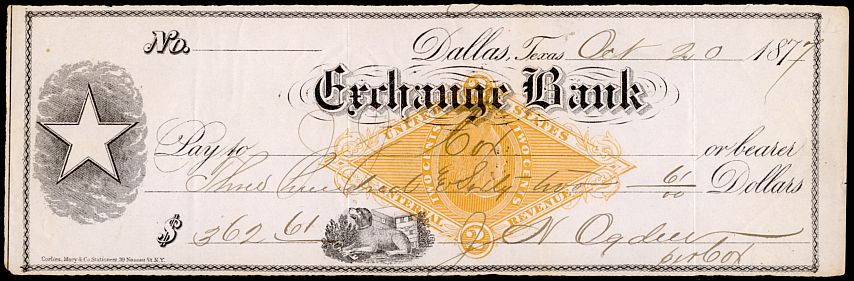

Figure 17. The dog in this vignette is lying in front of the safe with his front paws on the key, somewhere outdoors. The check was printed by Corlies, Macy and Company of New York for use in Dallas, Texas in the late 1870’s. It also contains a Type G revenue.

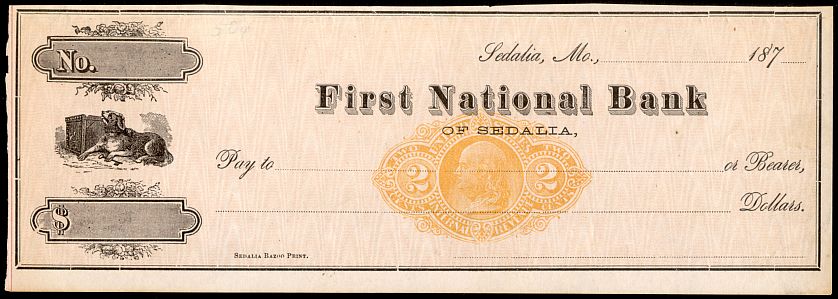

Figure 18 shows another variant of the dog, safe and key. It was printed by Sedalia Bazoo Print, and bears a Type F revenue.

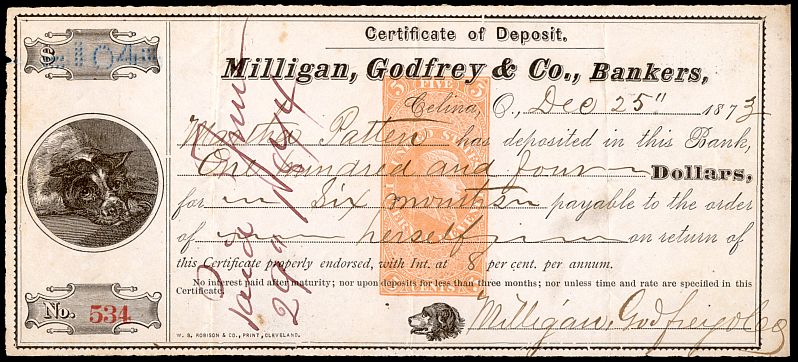

Figure 19. This dog, head view only, is also not a Newfoundland – but he does have a key beneath his paws to signify the security of Milligan, Godfrey and Company of Celina, Ohio on one of their deposit certificates. There is also another small head of a dog at the bottom of the instrument. The imprinted revenue is the five-cent type Q.

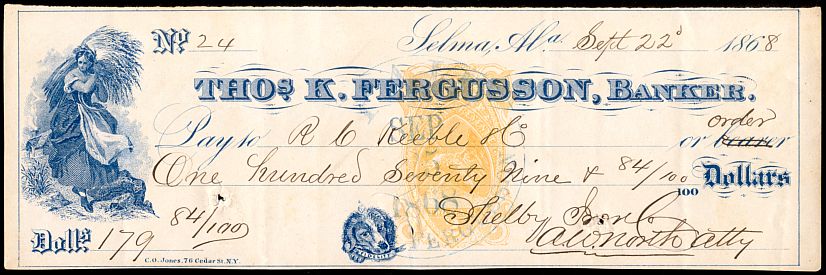

Figure 20. One more variation on the theme – a small dog head at the bottom of the check to signify “Fidelity” – it says so on his collar. No safe, no key, but the idea is there, and the animal might pass for a Newfoundland. The check, with a type B imprint, was imprinted for Thomas K. Ferguson of Selma, Alabama by C.O. Jones of New York.

It was an interesting project to go through my checks and other financial documents to see what I had containing canines. A similar profusion of eagles, stags, cattle, horses and sheep came to light, plus one check with a parrot, one with a buffalo, several with pigs, and a few with cats or kittens. Let your imagination roam, and you might have the beginning of a topical check collection already!

2007 Postscript – Landseer Vignettes.

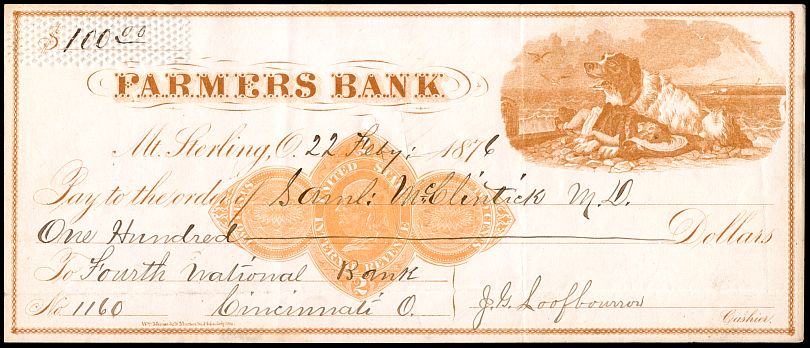

Sir Edwin Landseer, 1802 – 1873, produced many drawings and paintings featuring animals, particularly dogs. When I wrote the article above in 1997 I did not know just how many of the vignettes were taken from his work. For instance, the dog’s head in Figure 2 is from a Landseer painting called Saved. A vignette based on the entire painting is shown on the Farmer’s Bank draft below. Note that it was used just three years after Landseer’s death.

Likewise, the image in Figure 16 that I referred to as looking like a rawbone hound is also taken from a Landseer painting called The Friend in Suspense. In the original, what became the safe in the background is a table, and instead of a key next to the dog there is something that looks like the remains of whatever he took off the table and chewed up.

At this point I wonder if the hunting dog in Figure 1 comes from a Landseer painting. Likewise the dog on the college check in Figure 2 and the large vignette in Figure 19. If anyone can identify the source of any of the vignettes I will be glad to add the information to this Postscript.

This article originally ran in the April – June 1997 issue of The Check Collector.