by Bill Castenholz

The pigeon, painted red, white and blue, flew about the hall “in great agitation, not liking the tremendous roaring about him.” Jesse Grant stood at the front of the platform in “mute astonishment” while the tumult mounted. Behind him, the curtain rose, exposing a backdrop on which were painted likenesses of the goddess of Liberty and General Grant.”1

Thus General Ulysses Simpson Grant was nominated to be President of the United States of America at the Republican National Convention. The date was May 21, 1868. The place: the great Crosby Opera House in Chicago.

It was a glorious occasion and a great honor to have the opera house used as the place where this American Hero was nominated to the highest office in the land. But it was not the first time great excitement had been felt within the walls of this magnificent structure. Nor would it be the last.

There had been the grand opening. It was to take place on April 17, 1865 with a presentation of Italian grand opera. But the assassination of President Lincoln three nights before caused a delay until April 20th. When the opening night did occur “a brilliant assembly of society heard `II Trovatore’ and marveled at the splendor of the place.

“Thereafter Crosby’s was the home of grand opera. Its auditorium rang with the voices of Kellogg, Hauck, Brignoli, Ferranti, Parepa-Rosa, Bellini, Castle and a host of other far-famed singers. The Shakespearean plays of the day had their most sumptuous settings in this place.”2

Needless to say there had been great excitement in October, 1871, when the dreams of U.H. Crosby went up in smoke. Whether it was Mrs. O’Leary’s cow or some other source, the conflagration destroyed about 18,000 buildings over an area of approximately 2,000 acres. The Crosby Opera House certainly must have been one of the most spectacular edifices to have perished.

But there was another very exciting time for Crosby’s. It culminated on the 1st of October, 1866. And before it was over, thousands were involved in a “lottery” which has provided us with one of the most fascinating pieces of revenue stamped paper ever to have been produced. The story is an interesting one.

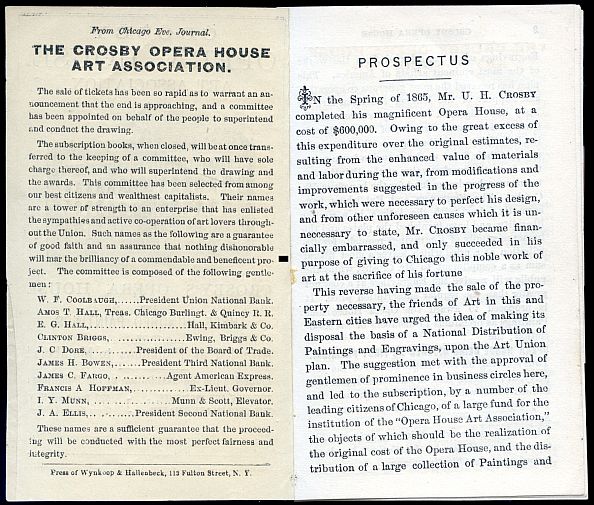

“In the Spring of 1865, Mr. U.H. Crosby completed his magnificent Opera House, at a cost of $600,000. Owing to the great excess of this expenditure over the original estimates, resulting from the enhanced value of materials and labor during the war, from modifications and improvements suggested in the progress of the work, which were necessary to perfect his design, and from other unforeseen causes which it is unnecessary to state, Mr. Crosby became financially embarrassed, and only succeeded in his

purpose of giving to Chicago this noble work of art at the sacrifice of his fortune.”3

Thus began the “Prospectus” for the great Crosby Opera House Art Association lottery. The prospectus went on to say, “This reverse having made the sale of the property necessary, the friends of Art in this and Eastern cities have urged the idea of making its disposal the basis of a National Distribution of Paintings and Engravings, upon the Art Union plan….”

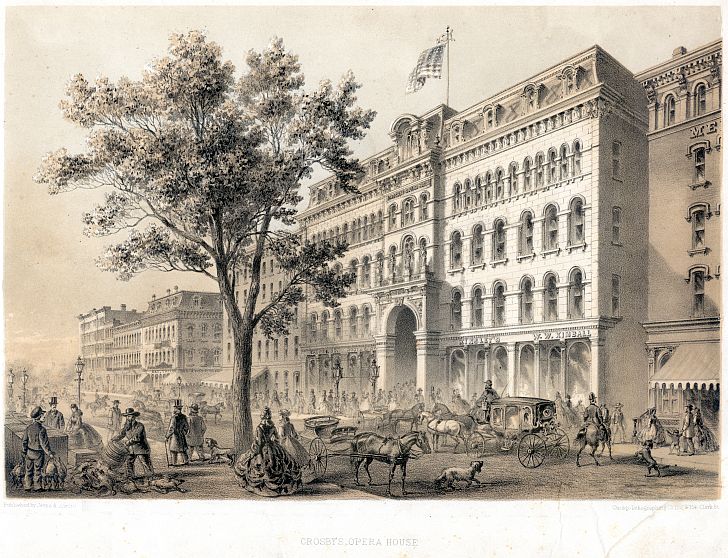

U.H. Crosby had come to Chicago from the East in 1850. After making a fortune in the liquor

business, he determined to construct a monument to the arts, one to be the most outstanding in the

country. What resulted was the Crosby Opera House. Located on the north side of Washington Street, between State and Dearborn, it was indeed a fabulous and lavish structure.

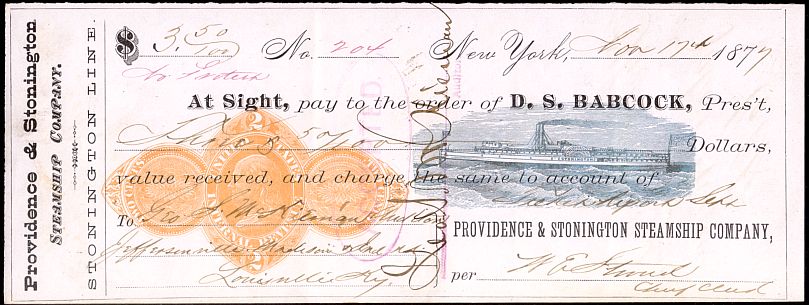

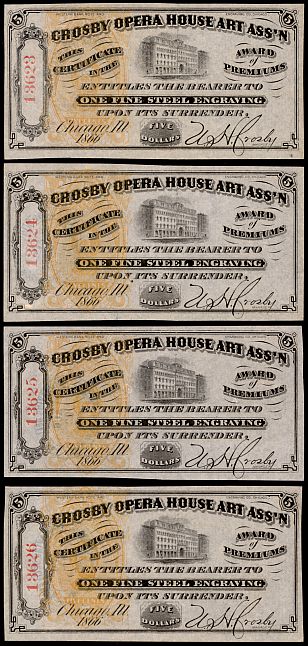

Figures 1 and 2. A set of four consecutively-numbered Crosby Opera House Art Association certificates and the receipt, dated August 22, 1866 which accompanied them. The imprinted revenue stamp, an RN-P5 in orange, paid the required five cent federal tax on a certificate. The “certificate” was carefully worded, as was the prospectus, to avoid any mention of the word “lottery.” These certificates were delivered to a firm in Keesville (sic), New York.

What brought this great civic project to such a desperate point? And how was it to be retrieved?

“With its art gallery of paintings and sculptures, Crosby’s was all very wonderful, but as an investment it was top-heavy and virtually ruined the man who built it. At a crisis in his affairs friends of Crosby organized an association and decided to dispose of the house by lottery.”4

Thousands of beautifully produced certificates were sold for $5 each. They promised to award each holder with a fine steel engraving. Actually, in addition, the purchaser had a chance to win one of three hundred and two prizes. There were 301 very significant pieces of art, including a number of oil paintings by renowned artists and an original life-size bust of Abraham Lincoln in carrara marble. But the grand prize was the actual Opera House itself!

“Most of the purchasers lived in Chicago, but nearly every state in the Union was represented. As the day for the drawing approached expectancy was on tiptoe. Hotels were jammed with incoming holders of certificates. Hundreds slept in saloons and railroad stations the night of 30 September, 1866*. The next day there was a terrific crush at the opera house when the doors were thrown open.

“The drawing on the stage was under the supervision of a committee of staid business men from Chicago, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Detroit and Fall River, Massachusetts. In one great revolving device 210,000 numbered cards were placed. In a small one were 302 tickets, representing as many articles to be raffled. Drawings from each were made simultaneously, the holder of the drawn ticket from the large wheel being in each case the winner of the prize designated by the number on the ticket of the other wheel.

“Excitement was intense when, well on in the drawing, ticket 58,600 called for the grand prize, the Crosby Opera House. The holder of the lucky number was not present, but he proved to be A.H. Lee, of Prairie du Rocher, Illinois.

“Couriers on horseback notified Lee that night as he lay peacefully in his bed in the little town. A few days later he came to Chicago and, according to his statement, sold the opera house back to the builder for $200,000 in cash. In the summer of 1871 the house was overhauled at a cost of $80,000, and fell in ruins in the fire of that year.”5

* Incorrectly stated in the original as January 20.

1. McFeely, William S., Grant: A Biography, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1981, p. 277, being a direct quote from the New York Herald, May 16 1868.

2. Hills, Frank K., “Editorial Comments and Current Topics,” Weekly Philatelic Gossip, Vol. X, No. 40 (Jan 2, 1926), p. 960.

3. Crosby Opera House Art Association (prospectus describing the “lottery”), no date (circa 1866).

4. Hills, Frank K., “Editorial Comments and Current Topics,” Weekly Philatelic Gossip, Vol. X, No. 40 (Jan 16 2, 1926), p. 961.

5. Ibid.

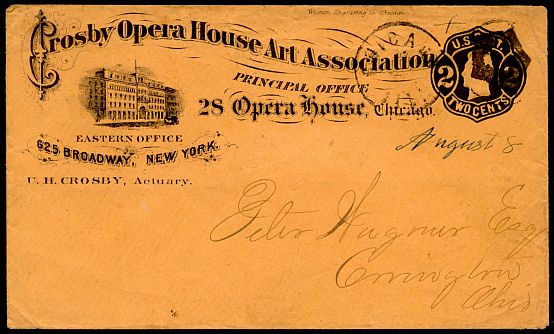

Figure 3. The envelope used to mail the brochure describing the scheme at the circular rate of two cents. It is a stamped envelope of the Jackson Die 3 type issued in 1864.

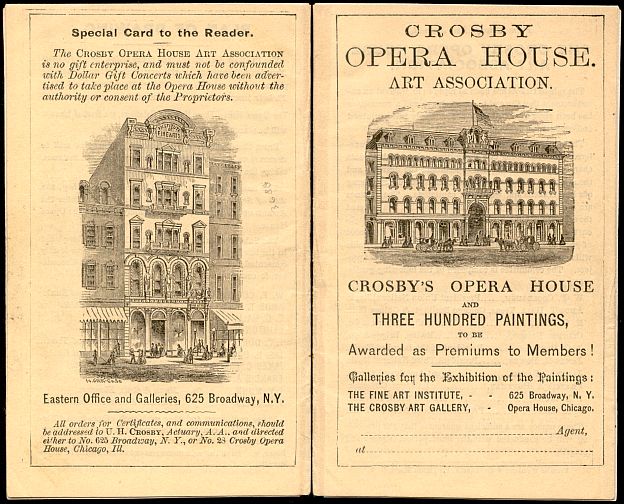

Figure 4. The back and front covers of an eighteen-page prospectus outlining the reason for, and method of disposal of, the art objects and the opera house itself.

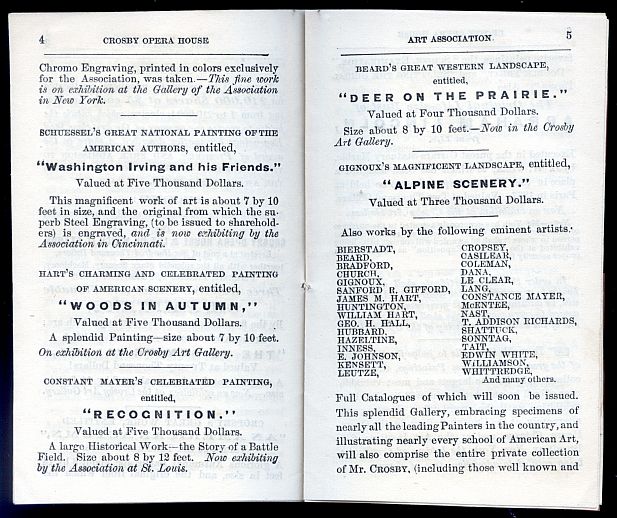

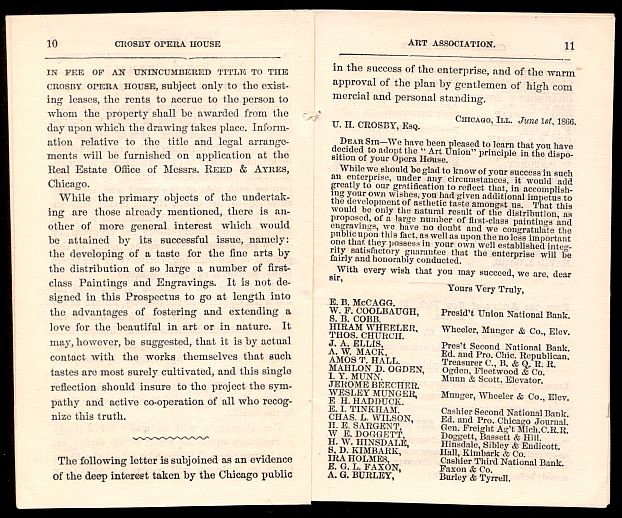

Figures 5 and 6. The first four pages of the Crosby prospectus.

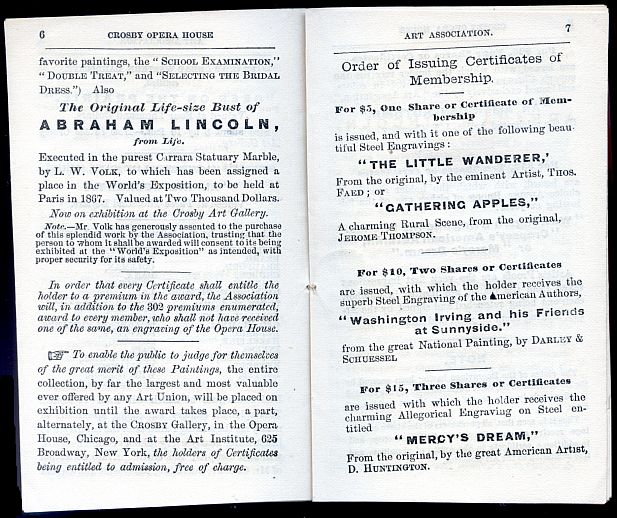

Figures 7 and 8. The next four pages of the Crosby prospectus.

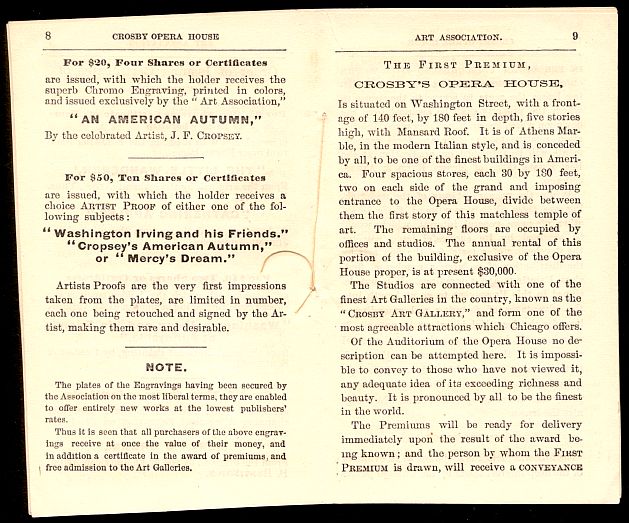

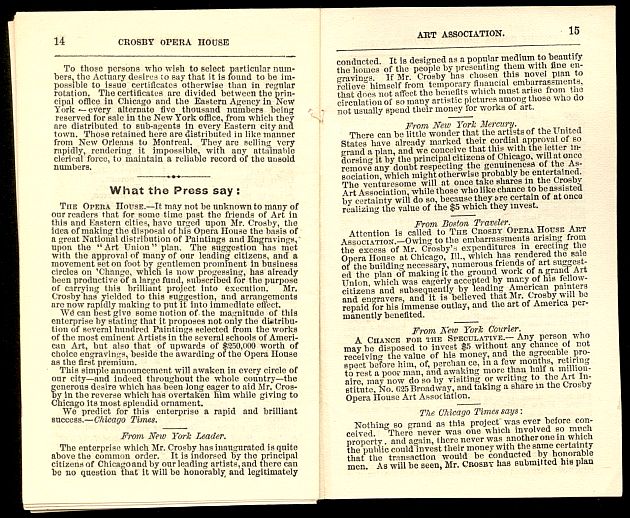

Figures 9 and 10. The next four pages of the Crosby prospectus.

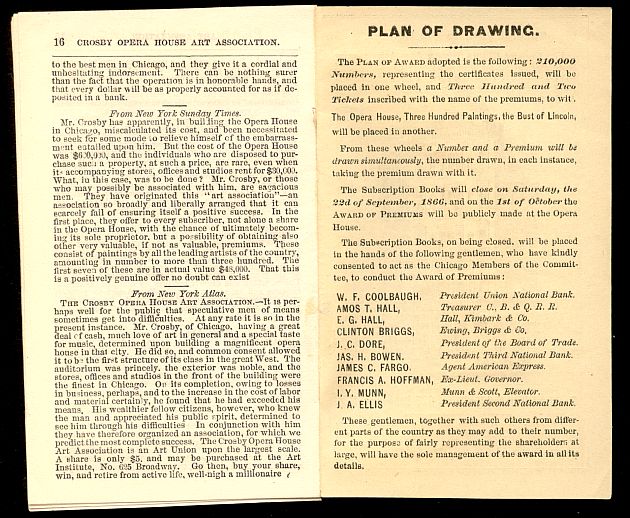

Figures 11 and 12. Another four pages of the Crosby prospectus.

Figure13. The final two pages of the Crosby prospectus.

Figure14. An unsevered pair of tickets. Does anyone know of any others, or any larger unsevered multiples?

Postscript – A view of the Crosby Opera House before the great Chicago fire.

The original article ran in the January – March 1997 issue of The Check Collector.